by Boston Pride

Picture this: whitewashed wooden colonial buildings and churches, the occasional mosque, a few Hindu shrines, and Dutch road signs, all surrounded by lush tropical growth. This is Suriname, a small republic north of Brazil. You’re forgiven if you’ve never heard of it. Although located on the South American mainland, it’s culturally much closer to the Caribbean. Another atypical thing about Suriname: it is one of the few places in the Caribbean to openly celebrate Gay Pride.

Suriname has just over half a million inhabitants, most of whom live on the Atlantic coast. Pristine tropical rain forest covers large parts of the country. European plantation owners brought in enslaved people from West Africa in the 17 th and 18 th centuries, followed by indentured laborers from China, India, and Indonesia, amongst other places. As a result, Suriname today is an incredibly culturally diverse country, where you can savor localized Asian cuisine with kawina and kaseko, music with a distinct African feel, blasting from the speakers. In the hinterland, Maroon and Amerindian communities maintain their tribal traditions.

Many Caribbean nations formally outlaw homosexuality; Suriname does not. “Yet within each of Suriname’s many ethnic communities and religions there is a sense of taboo towards same-sex relations, exacerbated by the large measure of social control that comes with any small society,” explains Faisel Tjon-A-Loi, chairman of the LGBT Federation Suriname, a coalition of local LGBT organizations that has presented Suriname Pride since 2011.

LGBTQ people in Suriname are facing discrimination and rejection. Pentecostal churches loudly proclaim homosexuality to be a sin. In the Asian communities, gay people are forced into arranged marriages. Suriname’s already high suicide rate is even more of a risk to LGBTQ people due to discrimination. Politicians are loath to offend their constituencies by championing gay rights. Suriname maintains close ties with its former colonial overlord, the Netherlands. Yet the LGBTQ emancipation over there is not always helpful; opponents occasionally frame homosexuality as wan witi man sani, in the local Creole: “a white man’s thing.” As recent as 2014, a local dancehall group produced a song calling for gays to be shot in the head, causing a national controversy.

And yet, last October three Amerindian young men wearing tribal headgear and high heels proudly walked at the front of a modest, but jubilant, Pride march through the historic center of Paramaribo, Suriname’s capital. It was the crowning celebration of a month of LGBTQ-related events, ranging from debates about LGBTQ and labor rights to a transgender photo exhibition and an international gay film festival.

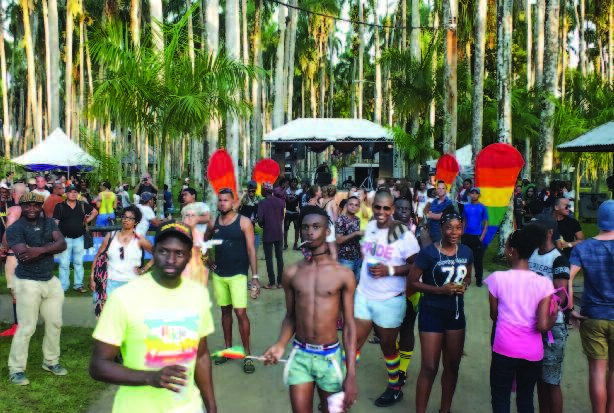

Locals party at the annual Pride Festival. Credit: Ana Bent.

Suriname has seen unlikely progress when it comes to gay tolerance. Patrick Liesdek is active in the Gay History and Archives Suriname project. One incident of gaybashing in the 1970s that he unearthed involved an angry mob throwing stones at a house where a private gay party had taken place, causing the owner to flee the country. Gay people were forced to live in the shadows of society for decades.

“But at some point, I was sick and tired of having to go to all these shady places just to have a drink,” says Liesdek. In 2001, he made the bold move of opening Suriname’s first openly gay bar, where a small but growing number of straight allies got a warm welcome, too. “I could have never imagined the success the Suriname Pride would turn out to be,” Liesdek confides. “Back then, I had trouble putting pictures of the bar on my website because the customers didn’t want to be recognized. Now, if the younger generation spots a camera during Suriname Pride, they run towards it!”

Ideas about organizing a Pride event in Suriname had been going around in the community for a while, when in 2011, Ronny Asabina, a member of parliament, declared in public that “gays should be eradicated once and for all.” The statement triggered intense debate in society, and LGBT Federation Suriname decided it was finally time for a public sign of defiance. Suriname Pride was born.

Suriname maintains close ties with its former colonial overlord, the Netherlands. Yet the LGBTQ emancipation over there is not always helpful; opponents occasionally frame homosexuality as wan witi man sani, in the local Creole: “a white man’s thing

Even leaders within the community had reservations when the first Pride was organized in 2011. The organizers decided on a nonconfrontational approach. “The first few Prides focused on projecting a positive image of LGBTQ,” explains LGBT Federation Suriname chairman Tjon-A-Loi. “Outright political demands were initially eschewed, instead inviting the Surinamese public to apply their ‘live-and-let-live’ mentality to LGBTQ people and same-sex relations.”

After a few years, LGBTQ activists felt emboldened to raise more controversial issues. LGBT Federation Suriname started urging the Surinamese government to develop specific policies for the LGBTQ community. Country visits by the Human Rights Commission of the Organisation of American States (OAS) helped to put the matter on the agenda by bringing more media attention to LGBTQ rights and mandating annual government reports to the commission.

“Suriname Pride not only brought people from the LGBTQ community together, but allowed us to reach out to allies and difficult-toreach target audiences,” reflects Tjon-A-Loi. “Even though the Surinamese economy is going through tough times, the support of the business community during the 2017 edition was overwhelming.” He says that local enterprises are very committed to promoting equality between straight and LGBTQ employees. Hundreds of businesses flew the rainbow flag from their premises.

For the future, Tjon-A-Loi’s mission is straightforward. “All Surinamese should be able to say, ‘I’m OK, whatever my sexual orientation and gender identity,’” he explains. “To me that means being valuable, being accepted as who you are, being allowed to be yourself, and being significant in every stage of your life.” Together with his LGBT Federation Suriname team, he’s committed to making the next Suriname Pride even more instrumental in transforming Surinamese society.

Ewout Lamé is a journalist and member of PAREA Association of Gay Professionals Suriname.